*WARNING: Spoilers ahead. This one’s been out for a while though, so you better sock-hop to it and watch it already.

We’re switching gears this week and ditching gothic castles for the hallowed halls of Dunsfield University. We’re of course talking about Monster on the Campus (1958), another offering from Universal. This movie belongs to a very different horror cycle from the one started by Dracula in the 1930s – one defined by a post-World War II scientific and technological boom, as well as Cold War concerns of nuclear conflict, communism, and space exploration. It’s often seen as the last hurrah for Universal monster movies of the classic era, and it certainly reeks of a sputtering subgenre.

Prehistoric creatures make for excellent horror movies: see Jurassic Park (1993), Jaws (1975), The Meg (2018), and Piranha 3D (2010), among others. Dinosaurs are no-brainers for prehistoric horror. The rest of the prehistoric creatures that filmmakers seem to lean toward are ancient fish, and you have to admit that movies about huge, aggressive sharks and viscous piranhas at least make you pause before getting into the water.

Before any of those movies, however, was this one; Monster on the Campus is the original prehistoric fish horror… kind of. Let me explain a bit about the fish in question.

THE FISH IN QUESTION

Twenty years before the making of this movie, just before Christmas 1938 in East London, South Africa, naturalist and museum curator Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer received a phone call from a local fisherman. She had a standing agreement with the fisherman, who frequently called her to pick through loads of fish on his trawler for potential specimens to go in the natural history museum. Among the piles of slimy sharks, she found what she would later describe as the most beautiful fish she had ever seen. About five feet long, with four stubby, leg-like fins and brilliant blue scales, the fish was not one she recognized. She decided then and there that it would need to be preserved and shown to an ichthyologist.

Somehow Courtenay-Latimer convinced a taxi driver to transport this massive fish back to the museum, where the resident taxidermist preserved and mounted it. She got in touch with J.L.B. Smith, a fish expert who worked as a curator in various museums along the South African coast. He identified the specimen as an ancient species of fish called the coelacanth (scientific name: Latimeria chalumnae, after Courtenay-Latimer).

Fossil records of the coelacanth go back more than 410 million years. At one point there were about 90 different species of coelacanth worldwide in both marine and fresh waters. Today, there are only two known living species of marine coelacanths. What makes Courtenay-Latimer’s discovery so incredible is that the coelacanth was thought to have gone extinct about 65 millions years ago – so it was a bit of a shock to find one alive and snapping at the fisherman who dragged it up.

The elusiveness of the coelacanth is largely due to its habits as a deep-sea drift feeder. The fish drifts along currents and eats whatever small prey it encounters. The coelacanth must be doing something right, since it seems that the species assumed its modern form about 400 millions years ago – meaning that it has experienced minimal evolutionary change for hundreds of millions of years. In other words, it’s a living fossil.

The coelacanth might not be as flashy or terrifying as a great white shark, but then again it’s not the monster in this movie. Rather, the amazing minds at Universal decided that this living fossil could be a great catalyst for the creation of a much scarier prehistoric monster to stalk campus.

THE AMAZING MINDS IN QUESTION

Monster on the Campus was directed by Jack Arnold and produced by Joseph Gershenson. Arnold is a man who I’ll talk about incessantly on this blog, as he is responsible for some of the greatest sci-fi/horror movies of the 1950s, including It Came from Outer Space (1953), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Tarantula (1955), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). Gershenson was the music director at Universal who created many of the music tracks that accompanied Arnold’s films. Arnold summarizes his feelings about the film’s 12-day production as follows:

“Joseph Gershenson was a very fine man who wanted like crazy to be a producer. Universal finally gave him his chance with Monster on the Campus and I was assigned to direct. The science fiction craze was dying out and I really didn’t want to do this kind of picture. But as a contract director I had little choice. I had to do it or risk being suspended. There were many problems with the script, but the studio liked it and wanted us to go right ahead with the picture. I tried very hard to do the best I could with it but we had a very tight schedule. If I had to do it all over again with more time and a little rewriting I could make it into a good picture. It’s not one of my favorites.” [From Directed by Jack Arnold by Dana M. Reemes, 1988]

THE PICTURE

Monster on the Campus begins with a fairly basic title card; it’s not as busy than the one we saw last week for Dracula, as it contains only the title of the movie. The title is set against a background depicting a shadowy, human-like figure, hunched over and reaching a hand out in front of itself. One thing this title card has going for it compared to Dracula’s is the lack of spelling mistakes.

When the opening credits dissipate, we watch as a van bearing the name “Dunsfield University Science Department” cruises down a road lined with Victorian mansions that I would give my right arm to live in. It looks to me like this scene was filmed on Colonial Street at Universal City, but I can’t find any confirmation of this anywhere.

A college student named Jimmy Flanders (Troy Donahue) is in the driver’s seat, and he pulls up to one of the houses and calls for Sampson. A German shepherd runs from the front steps of the house and jumps into the student’s front seat. There’s a sign on the front lawn of the house boasting the Greek letters phi lambda sigma (ΦΛΣ), which a cursory Google search tells me are the letters associated with the Pharmacy Leadership Society. This has no bearing on the film – in fact this particular society was founded three decades after it was released in theaters. I just enjoy the added lore that Jimmy lives in a pharmacy frat with his German shepherd.

Jimmy and Sampson drive under the wrought metal arches of Dunsfield University, a fictional school located in the fictional town of Dunsfield, California. While I can’t confirm whether or not Colonial Street was used for this movie, I can confirm that on-campus scenes were filmed at Occidental College in Eagle Rock, a suburb of Los Angeles.

Cut to a lineup of heads. Well, mounted models of the heads of various hominins (extinct ancestors of modern humans). Our lineup consists of the Piltdown Man, Pekin Man, Java Man, Neanderthal Man, Aurignacian Man, Modern Man, and an empty plaque dedicated to “Modern Woman.” Record scratch: hold up. The Piltdown Man?

Here we encounter our first of many instances in which this film proves my conspiracy theory: that there is absolutely no good science happening in the science department at Dunsfield. The bone fragments of the Piltdown Man were discovered in 1912 by amateur archeologist Charles Dawson near Piltdown village in Sussex, England. He estimated that the fragments were 500,000 years old, making the Piltdown Man a potential candidate for the missing link between humans and apes. Unfortunately for Dawson, in 1949 more technologically advanced testing became available and it was discovered that the bones were only 50,000 years old – so definitely not the missing link. The Piltdown Man was a paleoanthropological fraud, which Professor Blake (who we will meet shortly) most certainly should have known by 1958.

Not only that, but I’ve found another spelling mistake (I spoke too soon about the title card): there is a Pekin Man in the lineup, which doesn’t actually exist. The Peking Man, however, is a hominin that inhabited modern northern China up to 780,000 years ago.

Anyway, under the watchful eyes of the hominin heads, Professor Donald Blake (Arthur Franz), paleoanthropologist, wipes his hands at the laboratory sink and smiles over the body of a woman who lies prone on the lab table, plaster covering her face. He utters his first line: “Ah, there she is, the female in the perfect state: defenseless and silent.”

So he’s bad at science and an asshole.

Blake teases the woman about keeping her that way and even tickles her a bit, but quickly relents to her protesting squeals and frees her from her plaster face mold. Madeline Howard (Joanna Moore) hops off the table to inspect her hair in the mirror while Blake begins to wax poetic about the future of humanity. He claims that we are doomed, and that his hominin lineup will end with Modern Man unless we can learn to control the instincts we inherited from our ape-like ancestors. Madeline suggests that he should learn to control his instincts and stop being so pessimistic. They embrace, and we understand that they are romantically involved.

Later on we’ll learn that they’re engaged. But their relationship is fairly confusing to me – mainly in that it’s unclear if she is a student at Dunsfield or if she’s past her college years. She lives on campus, as her father is president of the university. The poster for this movie refers to her as a “co-ed beauty,” which would indicate that she’s a student. But a little later in the film she mentions that she needs to chaperone a dance, which would indicate that she’s older than the college students. I guess the distinction isn’t that important to the story, but I would dislike Blake a lot more than I already do if he were engaged to a student.

Madeline and Blake are interrupted from some almost-necking by the honk of the van outside. Blake goes to the window to talk to Jimmy and asks if he’s got “it.” Jimmy says he has, but it’s starting to thaw.

Jimmy has transported a coelacanth to the lab from Madagascar. While Blake exits the lab to meet him outside, Jimmy opens the back doors of the van. Water drips out onto the pavement. Sampson starts to lick the water up, but Jimmy shoos him away.

Blake opens the crate containing the coelacanth and explains to Jimmy that the species has not changed in millions of years. It’s a living fossil immune to the forces of evolution. Just as a side note, the fish model that they use for the coelacanth isn’t too bad. Although for some reason they gave it spikes running from its mouth up to its forehead – a feature that looks pretty rad but which real-life coelacanths definitely don’t have.

Madeline calls to Blake from the front door of the science building. She is greeted by Sampson, who snarls and barks at her menacingly. At least, menace was the intent, and they’ve even attached fake fangs to his front canine teeth to round out the look. But even as a cat person I can tell from his upright ears and wagging tail that Sampson is just a good boy barking on command. Just like he was trained, Sampson runs after Madeline, who turns and slams the door on him. Jimmy attempts to control his dog but Sampson fights back, biting his arm. Blake grabs the blanket that had covered the coelacanth’s crate and uses it to wrap Sampson up and carry him into the lab.

Blake takes Jimmy to get patched up in the office of Dr. Cole (Whit Bissell), another science professor on campus. Dr. Cole says that Sampson’s behavior doesn’t sound like it could be the result of a rabies infection, but he will keep the dog under observation overnight just in case. If by the morning he hasn’t shown signs of rabies, then Jimmy will be in the clear. Dr. Cole requests a saliva sample from Blake to be picked up later in the evening.

I’m no doctor, but immediately upon hearing this explanation I lost all faith in the entire science department at Dunsfield. Rabies is treatable in humans within a short window between exposure and the appearance of symptoms. Once symptoms appear, treatment is no longer possible – rabies is 100% fatal without treatment. In the 1950s, treatment for suspected rabies was gruesome. It consisted of a course of 25 vaccine shots in the abdomen of increasing concentration of the RABV virus (three shots on day one, two on day two, two on day three, and one each day for 18 days). Rabies can lay dormant in the body for days to weeks, and in some cases even months after exposure. But my understanding is that the general guidance over the years has always been to seek treatment immediately after exposure. The guidance has never been to wait it out and see if the dog looks like he has rabies in the morning. Maybe the deep dive into rabies I just did in order to write this paragraph has instilled an intense paranoia in me, but I don’t trust a medical professional who lacks a sense of urgency when rabies is potentially at play. I just don’t. Please get your pets vaccinated each year for rabies. My cat has never set foot outside and never will, but he still gets his shot every year.

Later that evening, Blake is working late in the lab with Sampson locked up in a cage in the corner. He notices Sampson is drinking water from a bowl, which I imagine is a good sign that there’s no rabies. However, when Blake approaches the cage, Sampson bares his massive fangs and growls at him.

Molly Riordan (Helen Westcott), the nurse from Dr. Cole’s office, appears at the lab to collect the saliva sample requested earlier. Blake shows her the dog and they discuss its condition. Blake notices that Sampson’s fangs resemble those of ancient animals. Molly notices that Blake is an attractive man and attempts to flirt with him. The professor gently rebuffs her advances and they are interrupted by a phone call from Madeline. She is checking on whether or not he will still be able to attend that night’s dance to help her chaperone, as they had originally planned. (Was it normal for college dances to have chaperones in the 1950s?) He says yes, but he’ll need to go home to change first and will pick her up a little before nine.

When Blake hangs up the phone, Molly points to the coelacanth sitting on ice in the middle of the room and asks what it is. Blake explains that it’s a coelacanth and that it needs to go in the refrigerator before it starts to spoil. Which is a relief to me personally, since that dead fish has been out at room temperature all day and it’s been bugging me. Blake grabs the fish with bare hands, placing one hand inside the fish’s mouth to carry it into the fridge. In the process of setting it down, he cuts his hand on the creature’s teeth. To make matters worse, while he moves the coelacanth’s crate out of the room, his injured hand slips and dunks into the disgusting, bloody fish juices pooled at the bottom of it. He proceeds to suck on his wound – which even Molly points out as stupid. The number of health and safety violations this supposed man of science has committed in the span of a few seconds is truly astounding.

Blake follows Molly out to her car to get her first aid kit. He starts to feel woozy and asks her to drive him home. When they reach his house, she tries to awaken the passed out professor – to no avail. She enters the house and uses his phone to call Dr. Cole. While waiting for the operator to connect her to the doctor, the front door handle slowly twists and a hairy hand reaches through. Molly turns and screams at something we can’t see.

Next we find ourselves at the home of Madeline and her father, Dr. Gilbert Howard (Alexander Lockwood), President of Dunsfield University. Dr. Howard is confused to find her still home and not at the dance. She says she is waiting for his “future son-in-law.” Her father excuses Blake’s tardiness – after all, it’s not every day that the science department scores a coelacanth. He says every paper in the country has a story about how Dunsfield attained the famous fish from Madagascar. The college’s investment in the fish will pay off in alumni donations. Madeline inquires as to whether it will pay off scientifically, to which her father replies that it will pay off in school growth, which is the same thing.

He’s interrupted by a phone call from Sylvia, who we will meet later. The couples have started arriving at the dance and the house mother isn’t there yet. Madeline has to leave for the dance without Blake. Her father suggests she drive by the science building on her way to check on him.

On her way into the science building Madeline is startled by a man who is inspecting Jimmy’s van, the rear doors of which are still wide open from earlier in the day. Madeline recognizes him as Mr. Townsend and they both agree to enter the building together to find Blake. Of course, when they unlock the lab doors and enter, he’s not there. Sampson certainly hasn’t gone anywhere, though. He no longer has fangs and he allows Mr. Townsend to pet him.

Madeline stops by Blake’s house, where she finds Molly’s car in the driveway. She pulls down the car’s sun visor and sees Molly’s name on the registration. Inside, the house is a wreck – furniture overturned and strewn about, the mirror smashed to pieces. She immediately calls the police. After hanging up the phone, she hears a moan from the bedroom.

She finds a similar scene of destruction in the bedroom, along with a portrait of herself torn in half. She follows the moans through the patio door off his bedroom and finds Blake on the lawn in the backyard. Madeline runs to him, and here we get the best-looking shot in the whole movie: the couple embraces and we can see Molly hanging dead by her hair from a tree just behind them. Blake notices the body and Madeline screams, alerting the police, who have just arrived on the scene. The officers run to lower Molly’s body to the ground and move Blake and Madeline inside the house.

Police Lieutenant Stevens (Judson Pratt) questions Blake about the events of that evening. Blake explains that he blacked out once they got to the house. Lt. Stevens is understandably suspicious of this story. An officer hands him a tie clasp found in Molly’s hand. Blake admits that it’s his, though Madeline attempts to cover for him by saying she’s never seen him wear it before. Blake is our square-jawed scientist with integrity, so he reminds her that she gave it to him for Christmas. Unfortunately, this show of virtue is not enough for me to forgive the misogyny or blatant disregard for lab safety protocols. Lt. Stevens appears to be thinking along the same lines, as he orders Blake to be taken down to headquarters.

The lieutenant is called into the bedroom by one of the other officers to look at Madeline’s torn portrait. He draws Lt. Stevens’ attention to a fingerprint in the corner of the picture. It doesn’t match Blake’s fingerprint, or any human print. And there’s a handprint on the glass door to the patio that looks suspiciously inhuman. This appears to be enough evidence to clear the professor of all suspicion, as Lt. Stevens begins to question Madeline about people who could potentially want to harm Blake. The search now turns to a mysterious third person who must have been present at the house that night.

We next see Blake at the front of his classroom, the coelacanth on display while he lectures to a group of students about the fish. He explained that the coelacanth as a species has evolutionarily stabilized, while man can still choose the direction he wants to take. When he dismisses the class, Jimmy and his girlfriend, Sylvia (Nancy Walters), ask after Sampson. They move to Blake’s back office, where Dr. Cole and Madeline are already examining the dog. Dr. Cole announces that Sampson doesn’t have rabies – which is great news that I’m sure Jimmy would have liked to hear much earlier in the day. Unfortunately, because he wants to run some more tests in order to determine where Sampson’s prehistoric fangs came from, Blake still doesn’t let Jimmy take his poor dog home. I fear at this point we’re teetering into a hostage situation. Blake attempts to show Dr. Cole the fangs, but to his confusion Sampson now appears to be in possession of a perfectly normal set of chompers.

Madeline tries to soothe a ruffled Blake by asking him to see her finished mask, which is now mounted on the “Modern Woman” plaque. Blake of course takes this opportunity to give another lecture about how close man is to savagery. Madeline has heard this speech before, and she has other things on her mind. She asks him a question that has been bothering her lately: was there anything between you and Molly? Blake is a smooth talker and knows how to say exactly what women want to hear: “Molly was very attractive but there was nothing between us.”

I can’t say I’d be personally satisfied with that answer (a simple “no” would suffice), but this seems to be exactly what Madeline wants to hear, as she gets a big smile on her face and thanks him before leaving the lab.

Lt. Stevens arrives exactly when she leaves, entering through the door labeled “Use Other Door.” This happens constantly throughout the movie – everyone uses the wrong door. I’m not sure if this is a gaffe or an intentional gag.

The lieutenant brings news of the investigation into Molly’s death: there is none. He asks Blake again if he can think of anyone who would have reason to want to hurt him. Blake claims he doesn’t know of anyone. Just to be safe, while the police try to figure out who is responsible for the murder, they are giving Blake a full-time bodyguard.

Lt. Stevens also mentions that he received the coroner’s report for Molly. She wasn’t badly injured at all, besides a few minor cuts and bruises. What killed her was heart failure – she died of fright. This revelation clearly unsettles Blake.

The next scene takes place in the lab again, this time later in the evening. Sgt. Eddie Daniels (Ross Elliott), Blake’s bodyguard, paces the room, clearly bored and impatient for Blake to finish his work for the evening so he can go home. He points out a dragonfly that has settled on the coelacanth, which is inexplicably sitting at room temperature outside of the refrigerator for the third time in two days. Blake shoos the dragonfly away and returns to the microscope he had been peering into. He quickly jumps to his feet and runs to his phone to ask Dr. Cole if he can stop by his office to show him something. He grabs the microscope slide and he and Sgt. Daniels leave the lab.

On the way to Dr. Cole’s office, they run into Sylvia and Jimmy, who want to know if they can have Sampson back. Blake tells them to wait for him at the science building. We follow the students on their way there, and along the way they start to hear a loud buzzing sound. They hide behind a tree to watch for the source of the noise, but being college kids they immediately forget about it and start making out. While they canoodle, a hand reaches through the branches of the tree, lightly touching Sylvia’s hair. Never fear, for the hand belongs to another college student who is also making out with a girl on the other side of the tree. Oh, those crazy kids.

At Dr. Cole’s office, Blake sets up his slide on a microscope, explaining that he saw crystallized bacteria. Dr. Cole is doubtful, since bacteria can’t crystallize. Lo and behold, when he peeks into the microscope he sees normal bacteria doing their normal swimmy thing. Dr. Cole becomes immediately dismissive and slightly prickish. He examines Blake’s hand and notices it’s infected. He makes fun of Blake for claiming to have been bitten by the coelacanth and Blake storms out of the office.

At the front door of the science building, the irritated professor tells Jimmy that he can have Sampson back, since there’s nothing wrong with him and they only imagined he went berserk. Sgt. Daniels excuses himself to find a call box to report to headquarters.

In the lab, the buzzing sound appears again. Blake opens the window blinds to find an enormous dragonfly hovering in front of him. The professor opens the window to let the giant insect inside – he doesn’t know what it is, but he wants it. He wheels the coelacanth out of the fridge to use it to attract the dragonfly, which immediately takes the bait. Jimmy and the professor manage to catch it with a net and Blake stabs it with a letter opener, killing it. He identifies it as a member of the genus Meganeura, an ancestor of the present-day dragonfly that has been extinct for millions of years.

It’s at this point, almost exactly halfway through the film, that Blake makes the connection between the coalacanth’s bodily fluids and the prehistoric creatures that have been popping up around him. He dismisses Jimmy and Sylvia, making sure they promise not to tell anyone about the dragonfly, as he would like to announce this scientific discovery himself.

In case you were starting to think that maybe Blake is capable of doing science, he manages to make another very serious health and safety violation while transferring the dragonfly to his work table. Its juices (not blood, since we established last week that insects don’t have the same blood that vertebrates do) drips right into the bowl of his pipe. I’ll give him some credit here, though: he does remember to put the coelacanth back into the refrigerator. But then he ruins my momentary pride by sitting down at his desk and smoking his pipe. The worst part of it is that he obviously knows something is off about it – he makes a disgusted face after the first initial puffs. Nevertheless, he continues to smoke it.

Almost immediately, Blake’s vision goes blurry and he becomes woozy like the night before. We watch from his distorted perspective as the dragonfly shrinks down to its normal size. We hear growls in the background.

Sgt. Daniels runs back into the science building when he hears crashing sounds from the lab.

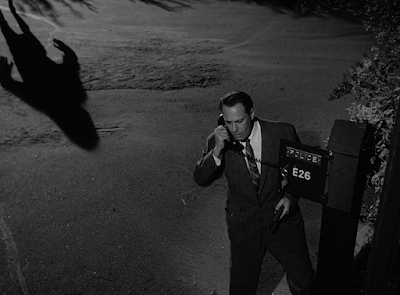

While he approaches the glass door, one of the hominin heads is thrown through it. He enters the lab to find it empty, with one of the windows broken. The sergeant climbs through the window and sees a man’s shoe on the lawn. He chases after a figure, firing off some warning shots. The mysterious figure manages to escape, so Sgt. Daniels finds the nearest call box to let headquarters know he needs more officers on campus. As he makes the call a hairy hand peeks through the shrubbery. We see the shadow of a figure approaching and suddenly the hairy hand grabs Daniels’ screaming face.

There’s a bit of a goof in this scene when Sgt. Daniels reports the number of the call box. The box is clearly labeled “E26” in large, bold letters, but the sergeant very clearly reports it as “B26.” Seems like he needed his readers.

Lt. Stevens, who had been on the other end of the phone, arrives on scene while a stretcher is prepared for the sergeant’s body. The bushes are disturbed and there are large, bigfoot-esque tracks in the dirt.

Somewhere else on the lawn, Blake wakes up, moaning and discombobulated with a shirt that’s torn to shreds. He returns to the lab, which is in a similar state. Blake picks up one of his shoes from the mess and clutches it to his chest while sirens wail outside.

At Madeline’s house, Dr. Howard looks at a copy of The Dunsfield Times, which boasts a front page photograph of the mysterious footprints and an article which quotes Dr. Donald Blake as believing the “clue points to subhuman.” Blake is there in the room, along with Madeline and Lt. Stevens. He explains to them all that he believes the footprints were made by an ancient version of man. Dr. Howard finds the idea completely ridiculous, concerns about alumni funding written all across his face. He says they must be fakes planted to trick the police, and they appear to be working.

Lt. Stevens admits he knows the footprints are probably fake and he knows who could have faked them. Blake is an expert in modeling parts of the human anatomy and knows how a primitive foot looks. But don’t worry – he doesn’t take this evidence into consideration at all. He explains that Blake could never take on Sgt. Daniels and win, and that the professor would never wreck his own laboratory. And anyway, the fingerprints didn’t match. So the killer can’t be Blake, but rather someone trying to implicate him.

Great police work, Lieutenant.

Back at the lab, Blake talks to the phone operator about placing a long-distance phone call to Madagascar to speak to Dr. John Moreau (a reference to H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau) at the scientific research institute. He tells the operator to charge the call to the science department.

A bit later in the day, while Blake is working on the coelacanth, his students show up for class. He’s confused, having been consumed by his work and forgotten about the lecture. To the delight of his students, he cancels class. Jimmy waits for his peers to filter out of the lab and then hands Blake his pipe, which he found on the lawn near where Sgt. Daniels was killed. It was good of Jimmy to give him the pipe. Personally, if the professor had held my dog hostage for days, I think that pipe would have found its way to the police.

Madeline enters the lab and asks to speak with Blake. He ignores her – he’s obsessed with the coelacanth’s blood and is annoyed by the interruption to his work. Madeline tells him her father is mad about the newspaper article and will be even more mad when he finds out Blake is canceling his classes. Blake insists he’s going to prove the existence of the subhuman. Madeline says that that’s the police’s responsibility and that he needs to rest.

The phone rings, and it’s Madagascar on the other end. Blake asks Madeline to close the door on her way out. She leaves, more annoyed than dejected, which is far more charitable than I would be in her position. On the phone, Blake asks Dr. Moreau how the coelacanth specimen was preserved. Dr. Moreau doesn’t seem to know the answer and explains he needs to call the Comoros Islands to find out. Blake tells him that Dunsfield University will pay the charges.

At home, Madeline tells her father about the long-distance call. Dr. Howard is not pleased by this news; apparently Blake has been on the phone with Madagascar for 76 minutes and counting at the price of $5 per minute. That’s $380, which in today’s money would be approximately $4,130. For one phone call! He calls Dr. Cole to come to his office and says he needs medical advice for Blake, to whom he intends to advise a leave of absence.

The paleoanthropology professor is still on the phone in the lab. It seems that he detected some level of radiation on the fish, which he verifies with Madagascar. Radiation, of course, is a major component of so many sci-fi/horror movies of this decade – when in doubt, radiation is probably the answer.

Drs. Howard and Cole enter Blake’s office. Dr. Howard scolds him for spending 88 minutes on the phone ($4,782 in 2024 money), all charged to the science department. Blake offers to pay the bill himself, but Dr. Howard says it’s not about the money. He suggests a leave of absence until the police clear up the whole matter of being framed for two murders. Blake is not impressed by the suggestion and insists that the police can’t find the killer – he’ll have to do it himself. In fact, he can show the men the secret of the killer’s metamorphosis, and he’d like the police to be there to witness his evidence.

Blake explains that when the coelacanth’s plasma is ingested by another organism, evolution is reversed and the organism reverts back to the behavior and appearance of its primitive form. He posits that the plasma would have the same effect on human beings, reverting the consumer back to a primitive anthropoid. Dr. Cole doesn’t buy this explanation. After all, the native people of the Comoros Islands have been eating coelacanths for centuries with no adverse effects. (Never mind the fact that coelacanth flesh is slimy, tastes awful, and causes diarrhea – Dr. Cole truly can’t be trusted it seems.) Blake argues that their coelacanths weren’t treated with gamma rays to preserve them for shipment. The gamma rays kill the bacteria that would normally cause decay – which finally explains why Blake has insisted on leaving that dead fish out at room temperature for hours at a time.

The scientific logic here is 1950s sci-fi at its best – it makes sense if you squint and don’t glance at any peer-reviewed papers from the past several decades. Unfortunately, Blake’s logic falls just short of the appropriate conclusion. He suggests that someone must have snuck into his lab and accidentally inoculated themselves with the coelacanth plasma. The second time would have had to be on purpose though, since no man could make the same mistake twice… Right?

Drs. Howard and Cole seem skeptical of this theory, and perhaps a bit accusatory. And suddenly the reality of the situation seems to become abundantly clear to Blake. When Lt. Stevens and his officers arrive in the lab, Blake backtracks, saying that his claims of a subhuman man on campus are a gross exaggeration and that he doesn’t have anything to show the police after all. He admits he needs rest and would like to take a leave of absence. Dr. Howard offers him his mountain cabin for some much-needed rest.

Rest is not exactly what Blake has planned, though. You know what they say – you can take the scientist out of the lab, but you can’t make him stop experimenting… or something like that. At the cabin, Blake has set up an elaborate system to test his latest theory: that he might be the murdering anthropoid.

Back on campus, Sylvia and Jimmy visit Madeline at her home. Something has been bothering them – they confess to having seen the giant dragonfly in the lab. They hadn’t said anything before because of their promise to not steal Blake’s scientific glory. But now they suspect that there might be some truth to the subhuman murderer theory. Madeline calls her father to say she’s driving up to the cabin immediately to see her fiancé.

At the cabin, Blake begins to explain his experiment on a tape recorder. He is interrupted by a knock on the door. It’s Tom Edwards (Richard H. Cutting) from the forestry service, and he’s come to check if Dr. Howard is using the cabin. Tom appears suspicious of Blake (as he should) but leaves. The professor resumes his experiment, injecting himself with the coelacanth plasma.

Finally, we see the monster for the first time. We watch the first portion of his transformation as his face and hands become hairier and hairier. Then we see his face with the full rubber mask. Now, a lot has been said about this particular mask; unfortunately, it’s not equipped very well, since we can see the bottom edge of it against Blake’s chest. We can also occasionally see Blake’s human teeth behind the jagged row of the monster’s fangs. It’s not the best monster mask I’ve seen, but it’s par for the course in terms of 1950s masks.

The design of the monster itself is fairly interesting. It looks like a cross between a neanderthal and an ape, with sharp fangs and bushy eyebrows perpetually frozen in a menacing frown. This mask was actually repurposed from the mask for Mr. Hyde in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953). But because the anthropoid monster in this film wears the same clothes that Blake was wearing when he injected himself, it wears a plaid button-up shirt tucked into khakis with a preppy-looking belt. It makes for an overall kind of goofy look.

Bud Westmore is credited for the makeup in this film. He was a part of the famous Westmore family in Hollywood and the head of Universal’s makeup department for 24 years. It’s unclear how involved he was in the making of the monster’s mask – Westmore had a history of taking credit for creature designs that were not his (stay tuned for my review of Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) for more on that).

The monster immediately gives in to its primitive instincts, going on a rampage. He knocks over the table with the tape recorder and throws chairs. He sets off a trip wire attached to a camera, which further agitates him. However, the anthropoid is not so primitive that he doesn’t know a good weapon when he sees one – he finds an ax by the fireplace and gives it a few tentative swings. In fact, he’s a quick learner. He uses the ax to smash through one of the cabin windows to climb through it. He may have mastered tools, but doors are still a mystery to this subhuman man.

Madeline speeds past the ranger station and honks at a figure walking in the middle of the road. She screams when the figure turns around, revealing itself to be the monster wielding an ax. She swerves off the road and down the hill, crashing her car. The anthropoid approaches her unconscious body. He draws his arm back to swing at her with the ax but stops himself. He reaches down to stroke her face instead. Tom, who had heard Madeline’s screams, comes running and asks if she’s been badly hurt. The monster turns and scares Tom away, then carries Madeline into the brush. I feel bad for Joanna Moore in this scene because, while she is pretending to be a passed out Madeline, the actor who plays Blake as the monster (Eddie Parker) appears to struggle to get a good hold on her. While lifting her he bangs her knees against the car door and jostles her up quite a bit.

Tom books it back to the ranger station and calls the Dunsfield police to report the monster sighting. Then he grabs his gun and runs back out to track him down. He swings by the Howards’ cabin and finds the wreckage there. Tom calls out to Blake. Nearby, the monster has carried Madeline to the top of a hill and set her down in the grass. He hears Tom’s calls and steps away from Madeline to locate them. Madeline wakes up, sees the monster, and starts screaming. Before she can run away, the monster grabs her and pulls at her hair.

Tom hears her screams and runs over to help. By the time he arrives, Madeline has fainted again and the monster has carried her to a new spot to lie her down gently. Tom steps on a twig, alerting the monster to his presence. He opens fire on the anthropoid, who responds by throwing the ax with impeccable aim, right into the ranger’s face. Which is impressive for someone who just discovered the ax a few minutes ago.

The gunshot wakes Madeline, who again runs away. This time she manages to escape, as the monster’s pursuit is slowed by the bullet wound in his shoulder. He falls to the ground in pain.

Madeline sprints into the cabin. She yells for Blake, and when she gets no response from the house and turns to run out of there, she runs right into her fiancé. He’s back in his human form and looking worse for wear in his tattered plaid shirt (the khakis are intact still). Blake comforts her for a few seconds then pushes her aside to grab the film from the camera. He develops it to see a picture of the monster flinching from the flashbulb.

Now, I like Madeline. In my eyes, she’s either a student or a young woman who fell for the charming scientist who cares more about his work than he ever will about her. She’s been ignored and belittled by him at every turn. I feel bad for her. I’m rooting for her. But what is her reaction upon seeing the picture of the monster? I want to say it was an intelligent remark, maybe the dawning of an important realization. Alas, she says: “Donald, he’s wearing your clothes!”

Lt. Stevens, Dr. Howard, and an officer burst into the house. Madeline states that Blake has killed the monster, but he corrects her and tells the gentlemen that he knows where the monster hides – and he can show it to them. He sends them along ahead of him and shares one last kiss with Madeline. He tells her to stay in the cabin and that if she’s still alive, then the beast must have loved her at least a little.

I am slightly confused at this point, since we just saw Tom shoot the anthropoid in the shoulder but now that Blake is in his modern human form he seems totally healed?

Undeterred by a little bullet to the shoulder, Blake leads the men out into the hills, where they find Tom’s body. The professor tells them that he can find the monster but he must do it alone. They can wait at a distance and shoot to kill once he drives the monster out. The men object to him going off on his own, so Blake asks Dr. Howard to accompany him over the hill. Once alone, Blake engages Dr. Howard in another lecture on the savagery inherent in all men. It has all the earmarks of a villain confession speech. Then he rolls up his sleeve and once more injects himself with the coelacanth plasma.

Blake transforms into the anthropoid and chases after Dr. Howard, who runs down the hill shouting, “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!” The lieutenant ignores these cries and immediately sinks a round of bullets into him. The monster lies sprawled out on the ground, dead. The men watch as he transforms back into Blake in a series of transition shots that are reminiscent of those used during the Wolfman movies of the 1940s. They stand puzzling over his body while the end card appears.

FINAL THOUGHTS

And that’s the film. Critics have correctly pointed out that this film in the hands of a lesser director would have been a schlockfest. And while it’s no Citizen Kane, it’s a quality entry for the teen monster exploitation market and benefits greatly from Arnold’s masterful direction and natural ability to build suspense.

The ending is fairly nonsensical – there’s no real reason for Blake to have injected himself willingly at the end, except to prove to the men who doubted him that he was right about the coelacanth plasma. He very well could have taken that knowledge with him to the grave and married Madeline. Sure, he would have to spend quite a lot of time working to pay for that long-distance call to Madagascar, but it would have been a better life than the death he got.

I don’t dislike the bleak ending, though. It’s what made me like this movie to begin with. The handsome, square-chinned scientist is supposed to get the girl and defeat the monster – that’s how all 1950s sci-fi/horror movies end. But in Monster on the Campus, our square-chinned hero actually is the monster, and in an act of either self-destruction or heroic selflessness he destroys himself.

Another thing I enjoy about this movie is the brutality of some of the deaths. Seeing Molly strung up by her hair and Tom taking an ax to his face startled me the first time I watched it, as these are some of the more graphic and disturbing deaths I’ve seen from movies of this era. There’s no gore, but there’s a level of brutality about them that’s delightful to someone who has just finished rewatching Dracula (1931) about five times in the past week (we see literally one drop of blood and zero bites in that movie).

Monster on the Campus is a romp of a sci-fi movie that scratches a very specific itch for me. There’s nothing I love more than when 1950s screenwriters bend over backwards attempting to make the science explanations make any sort of sense. I delight in seeing the many creative ways they manage to make radiation the ultimate villain. And package that all as a teen monster movie? I’m in.

My main criticism is actually that there aren’t enough teens in this movie which has been marketed as a teen monster movie. I would have loved to see more of Dunsfield and its students, rather than stay in Blake’s lab the whole time and watch him flout every single OSHA regulation.

But in spite of its shortcomings and because of its quirks, I do recommend giving this movie a watch if you haven’t already. As of the writing of this review, you can stream it for free on Tubi – no account or subscription required.

Thanks for sticking with it! I hope you’ll join me next week, when we pay a visit to a dying woman with a pack of vulturous relatives and a veritable herd of cats under her roof.