*WARNING: Spoilers ahead. Although if you haven’t managed to watch this movie at some point in the past almost 100 years, that’s on you.

I can’t think of a better place to start this blog than on Valentine’s Day, 1931.

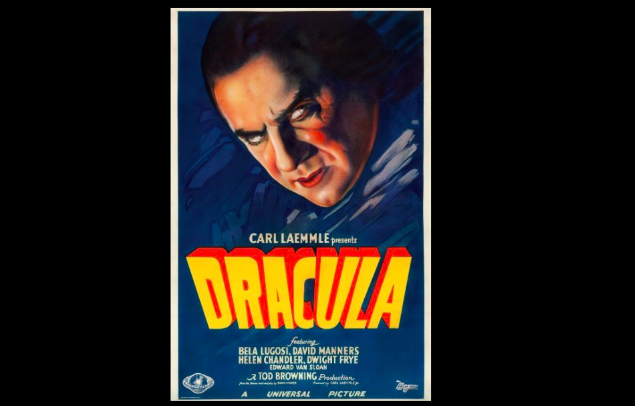

Movie-goers across the country flooded theater lobbies awash in flickering candlelight. Paper bats hung from the ceiling and patrons shuffled past Bela Lugosi’s penetrating gaze on movie posters which advertised “The Story of the Strangest Passion the World Has Ever Known.”

Dracula was released in some cities on Friday, February 13th, 1931 and in others on the following day – Valentine’s Day. The timing was perfect for a horror movie described as a “strange kind of love” story by Carl Laemmle, Sr., co-founder and owner of Universal Pictures. The timing of Dracula’s release was so seemingly perfect that it’s easy for modern audiences to forget the historical and economic circumstances in which the film was conceived – as they were anything but ideal.

The early history of Universal deserves its own blog post at a later date. However, in order to fully understand and appreciate how significant Dracula was in kick-starting Universal’s subsequent horror cycles, I’m going to give a brief overview here of that history up until 1931.

A STUDIO IS BORN

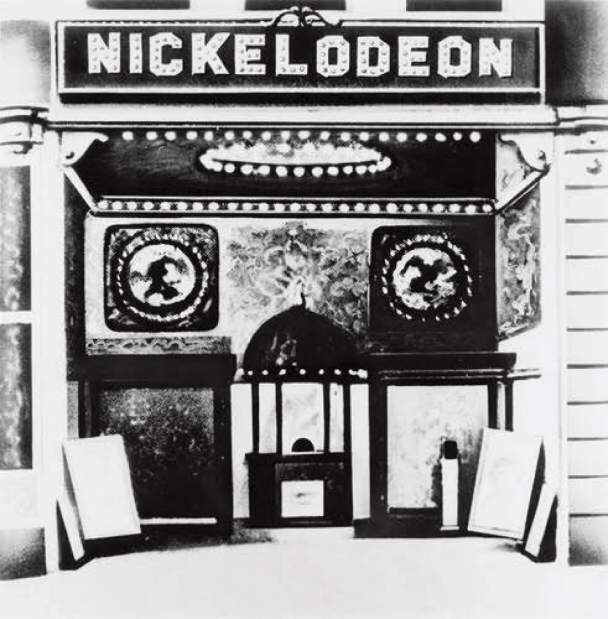

Universal was the brainchild of Carl Laemmle, a German who immigrated to the United States in 1884. He spent twenty years working in Chicago as a bookkeeper and office manager until the day he stumbled upon a nickelodeon and immediately saw the entrepreneurial potential such an establishment presented. He bought his first nickelodeon, called The White Front, in 1906 and soon thereafter created his own motion picture studio and production company. The Independent Moving Picture Company (IMP) was founded in 1909 in New York City and boasted a production studio in New Jersey.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company, also known as the Edison Trust, maintained a monopoly over all aspects of the burgeoning film industry, from production to distribution. Independent filmmakers like Laemmle quickly grew tired of the high fees demanded by the Edison Trust to show their movies in Trust theaters. Filmmakers also resented the expensive restrictions the Edison Trust placed on them, such as requiring the use of Trust film projectors and stock. They began to make movies secretly, using their own unlicensed equipment. The Edison Trust began to issue injunctions against the independent filmmakers, including Laemmle, for using cameras that they claimed infringed on their patents. Laemmle and his cohorts did the only sensible thing in this situation: they moved to Southern California, hoping distance would save them from the wrath of Edison and his patent company. By 1912 several struggling studios incorporated to form the Universal Film Manufacturing Company, to which Laemmle was elected president in short order.

Universal became a major player in the film industry during the 1910s and 1920s, profiting greatly from the wide variety of silent films it produced. I’ll certainly take a look at some of them – like The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925) – at a later date. But by the end of the 1920s, Universal was in trouble.

DEPRESSION WOES

The Great Depression began two years before Dracula’s release, when the stock market crashed in October 1929, forcing millions of Americans into unemployment and abject poverty. Movie studios quickly found that the industry wasn’t depression-proof; weekly attendance at movie theaters dropped by tens of millions of people, ticket prices necessarily lowered, and production costs associated with the newly-popular “talkies” more than doubled compared to the silent films of the previous decade.

In spite of the economic hardship – or perhaps due to the need to forget it for an hour or so – somewhere in the neighborhood of 70-80 million Americans visited movie theaters each week during the peak years of the Depression. Studios had to find a way to capitalize on this attendance to stay afloat.

Universal faced an additional struggle that other studios of the time did not: a major change in leadership. Just before the onset of the Depression, Laemmle appointed his son, Carl Laemmle Jr. (“Junior” Laemmle), as head of production in 1928. Junior Laemmle received stewardship of his father’s company as a twenty-first birthday present (my parents bought me a pint of Guinness for my twenty-first), and he was immediately tested in his ability to helm a sinking ship.

Whereas his father preferred to focus on producing as many pictures as cheaply and quickly as possible, Junior instead directed the studio to produce fewer, more expensive “prestige” pictures. There was greater risk involved in putting the majority of the studio’s assets into only a few movies at a time, but to Junior the benefits far outweighed the risk. And at first it seemed that this approach had some merit, as one of the first pictures he produced for Universal, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), won him an Oscar at the ripe age of twenty-two.

It was Junior who persuaded his father that horror pictures were worth taking a gamble on – a move which would ultimately help keep the studio afloat during the worst of the Depression. The first horror property Universal would realize in the sound medium was one that the company had discussed securing several times already in the course of its short history in Hollywood.

THE UNDEAD PROPERTY

Vampires have existed in American folklore for centuries. Articles about vampire “attacks” from around the globe appeared in American newspapers from the eighteenth century onward. One of the best examples of vampires as a part of American culture happened decades before Bram Stoker published his novel. As a reaction to outbreaks of tuberculosis in the mid-to-late 19th century, “vampire panic” spread across New England. At a time when infectious diseases were not well understood, New Englanders believed that homes in which several family members were ill were in fact being nocturnally visited by the undead – usually a recently deceased relative. This belief drove families to exhume the bodies of freshly buried loved ones and deal with the “vampire” in a variety of ways – from turning the body over onto its stomach to decapitating it and burning the internal organs.

Stoker’s novel was at least partly inspired by the case of Mercy Brown, which occurred in Rhode Island in 1892. In this case, a father exhumed the body of his daughter, Mercy Brown, after his wife and other children died within the span of a few years (most likely due to tuberculosis). Mercy’s body, which had been stored in an above-ground crypt at freezing temperatures during the worst of the New England winter, had not decomposed as much as anticipated. In fact, witnesses were baffled by her hair and nails, which appeared to have grown since her death. Her father saw this as proof that she had been rising from her grave at night and feeding upon her mother and siblings. He burned her heart and liver and forced his surviving son, who was sick at the time, to drink the ashes mixed with water. His son died two months later.

Dracula the novel was published in 1897 and soon gained widespread attention and popularity in America. The eponymous vampire was described as “cruel-looking,” with bushy white hair and eyebrows and “fetid” breath. It’s not difficult to see where Stoker might have taken some inspiration from the case of Mercy Brown. But how did his character transform from a stinky, hairy creature to the sexy, alluring Dracula we see in the 1931 film?

Part of it was surely due to the casting of the handsome and debonair Bela Lugosi. But the transformation of vampires in American culture from disgusting undead creatures to sex symbols was largely due to a poem written by Rudyard Kipling in 1897 – the same year Dracula was published – called “The Vampire.” In it, a female vampire is described not as a woman who drinks blood but as a woman who loves a man until she has taken everything from him. The first verse is as follows:

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and bone and a hank of hair.

(We called her the woman who did not care)

But the fool he called her his lady fair

(Even as you and I!)

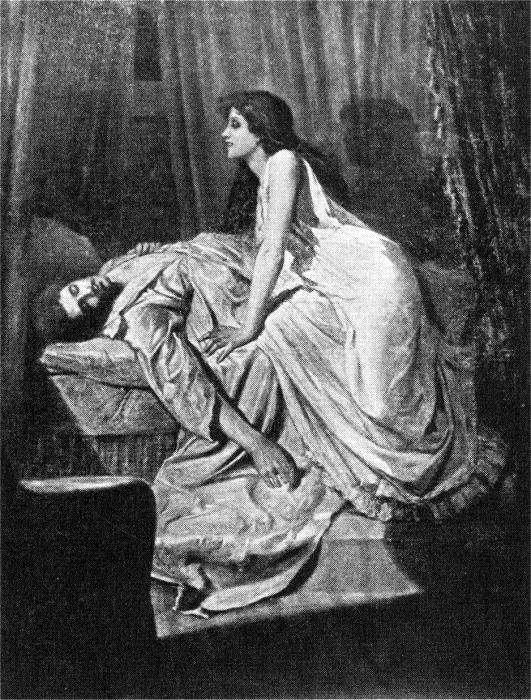

Kipling’s cousin, Philip Burnes-Jones, created a painting also called “The Vampire” (and also completed in 1897) which depicted a woman leaning over a dead man, having just drained him of his blood. Due to these works, the term “vampire” became a metaphor for a parasitic woman who used her charm and sexual allure to prey on innocent men. This type of vampire quickly became a stock character in plays and movies. The most famous of those films was A Fool There Was (1915), starring Theda Bara, the most iconic vamp of the era. Suddenly vamps were more than creatures of folklore – they were also seductive, beautiful, very-much-alive creatures who never considered drinking blood.

This is not to say that Stoker’s version of the undead vampire totally disappeared during the 1910s and 1920s. In 1915 Universal considered purchasing the rights to adapt Dracula but were dissuaded by the significant cost and the complicated legal processes that would be involved. The studio also acknowledged that the story itself was too expansive and gruesome to be translated into a silent film. Rumors that Universal was considering an adaptation appeared again in 1920 and 1925. In 1922, Nosferatu, an unauthorized German silent film adaptation by F.W. Murnau, was released.

Writer Hamilton Deane adapted the novel for the British stage in 1924, to resounding success. John L. Balderston was hired to Americanize the Deane play, which opened on Broadway in 1927 with Bela Lugosi in the starring role. Also in 1927, Tod Browning (who we will discuss shortly) directed London After Midnight, a lost film from MGM that reportedly shared some similarities with Stoker’s novel.

Probably due in part to the success of the stage play, Universal began earnestly pursuing rights to Dracula from Florence Stoker, the novelist’s widow. This also involved purchasing rights to the stage play from Balderston and Deane, which further complicated the process. Nevertheless, the studio acquired the rights in 1930 for $40,000 and soon a completed script was turned in. It was the product of several treatments and revisions completed by several men, including Fritz Stephani, Louis Bromfield, Dudley Murphy, and Garrett Fort. Fort is the only screenwriter credited for the final film.

The American public, with its longstanding interest in vampires, as well as a newer, sexier image of the creatures, was ready for a vampire film that would make horror history.

PRODUCTION

Production for Dracula began on September 29, 1930 with Tod Browning in the director’s seat – although this brings up one of many myths about the film that continue to percolate through the ranks of film critics and historians to this day. The idea that it was actually cinematographer Karl Freund, rather than Tod Browning, who directed the majority of Dracula has been oft-repeated to the point that it is now taken as fact. This myth comes solely from the recollections of David Manners, the actor who played John Harker.

“To be quite honest, Tod Browning was always off to the side somewhere,” he said in an interview years after the release of the film. “I remember being directed by Karl Freund, the photographer who came from Germany and had a great sense for film. I believe that he is the one who is mainly responsible for Dracula being watchable today.” Manners continues to say that he recalls Browning as being distant and “back in the shadows on set.” We have no other interviews from cast or crew members regarding Tod Browning’s level of involvement on set. Perhaps more importantly, we have no interviews in which cast or crew members describe Freund as having a more directorial role. Manners’ comments have been repeated for decades and have generated doubt as to who directed the film – to the point that Freund is credited on IMDb as a director of Dracula. This is not the only instance of David Manners saying something untrue that has since been adopted as historical truth.

Another common misconception about Dracula’s production – this time not based on a fib from David Manners – is that Bela Lugosi was only cast as a last resort when Lon Chaney, “Man of a Thousand Faces,” couldn’t play the part of the titular vampire. This is a gross misrepresentation of the situation. It’s true that Tod Browning and Lon Chaney had one of the most significant director-actor relationships of the silent era. Browning likely had been looking to make a Dracula adaptation as early as 1920, at which time it’s reasonable to assume he would have chosen Chaney in the starring role. In fact, Browning proved this assumption true in his choice of star for his 1927 silent film London After Midnight. Chaney starred as the undead killer in this much-sought-after lost film which was more of loose adaptation of the Deane-Balderston play than of the Stoker novel. However, by the time production was underway at Universal for Dracula, circumstances had changed considerably so that Chaney was no longer a viable option for the titular role.

By the late 1920s, Lon Chaney had managed to turn his fame during the silent era into success in the talkies. He was under contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) at this time and enjoyed a degree of star status there. MGM liked him so much that in 1929, when Universal requested Chaney’s services for some dialogue scenes in a part-talking reissue of The Phantom of the Opera (1925), Louis B. Mayer turned down the offer. Therefore it is unlikely that MGM would have been willing to lend Chaney to Universal for an entire picture, especially one which had already garnered a significant amount of attention in the press and trade papers. This is not to mention the exorbitant cost that Universal would have had to take on in order to secure Chaney on loan from MGM, who was paying him $3,750 per week.

In addition to the unlikeliness of a studio loan, there was one more significant reason that Chaney would not have been in the running for the part of Dracula: he died of throat cancer in 1930. He was ill and unable to work prior to the start of Dracula’s production and prior even to Universal’s acquisition of rights to the property.

So while there is no doubt that Chaney would have been at the top of Browning’s list for the role under different circumstances, it’s a disservice to Bela Lugosi to say that he came second to Chaney. By the time that Dracula was being cast, Chaney didn’t even factor into the conversations being had.

Quite a few names were floated for the lead role, but no matter who was the choice of the week in the trade papers, one thing remained consistent: Lugosi tirelessly campaigned for the part throughout pre-production. He made frequent remarks about the upcoming picture to reporters and remained in touch with the literary agent who had been involved in the selling of the play’s film rights. He later claimed to have acted as a representative for Universal during the bargaining of rights with Florence Stoker, although the evidence for this claim is muddy at best. There is proof of correspondence between Lugosi and Florence Stoker in which the actor attempted to broker a rights deal on behalf of MGM that would include himself as the star of the film, but there is no evidence that he did so on behalf of Universal at any point.

It’s unclear to what degree Lugosi’s persistent campaigning helped him secure the role, but in the end Universal decided to go with the Hungarian actor. Perhaps because they knew exactly what they were getting with Lugosi, who had starred in the original New York production of the Deane-Balderston play Dracula – The Vampire Play. Associate producer E.M. Asher, along with screenplay coauthors Bromfield and Murphy, viewed Lugosi’s stage performance as the Count and by late June 1930 there were rumors that Bela Lugosi was the studio’s choice in leading man.

Lugosi was hired for considerably less money than Chaney would have cost at the time: he was paid $500 per week over the course of 7 weeks of filming. This brings me to Lie #2 perpetuated by David Manners: Manners claimed that he made $2,000 per week during the filming of Dracula, making him the highest-paid actor in the film for a role that has arguably the least amount of screentime. Manners’ claim has been repeated over the years and has garnered a significant level of outcry on behalf of the comparatively underpaid Hungarian. While one could reasonably argue that Lugosi should have been paid more for his work on Dracula, Manners’ claim is a blatant lie. At the time of filming, Manners was under contract with First National Studios for a salary of $300 per week. A surviving legal agreement at the Warner Bros. archive at the University of Southern California shows that First National loaned Manners to Universal for $500 per week. Manners would have pocketed his usual $300 per week and First National would have collected the remaining $200, a practice that was typical for inter-studio loans. Manners therefore was not paid more than Lugosi and was not the highest paid actor on the film. That title goes to Helen Chandler, who was paid $750 per week.

I could go on and on about Bela Lugosi, his early career in Europe, and how he found his way onto the set of Dracula in 1931. That’ll be a topic for another day. I think it’s finally time to talk about the picture.

THE PICTURE

Dracula begins with a title card featuring a very familiar-looking Art Deco bat. Bob Kane and Bill Finger, the creators of Batman, never acknowledged that they took any inspiration for Batman or his iconic winged logo from Dracula, but they did admit admiration for the eponymous vampire’s gothic style. Interestingly, there is a spelling mistake on the title card. Carl Laemmle is listed as the “Presient” of Universal.

Accompanying the title card and full credits is the eerie, atmospheric Act II of Swan Lake by Tchaikovsky. We’ll hear this music a few more times in Universal horror movies of the early 1930s, including Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932).

The music of Dracula is often a source of criticism for modern viewers. Besides Swan Lake, there is only one other piece of music in the entire film: the overture from Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, which can be heard as diegetic music (music that is heard by characters within the story) during the opera scene. The film does not have an original score, which leads to long stretches of silence throughout that can be off-putting for modern audiences. In 1999 Philip Glass composed a score to accompany Dracula, which I personally find distracting and unnecessary. I highly recommend watching the original, score-less version of this movie.

One last interesting note about the sounds of Dracula: Jack Foley was responsible for the sound effects in this film. His work – on this film and others – was so profoundly important to the industry as a whole that sound effect artists are to this day known as Foley artists.

When the title cards fade we’re met with a shot of a horse-drawn carriage moving swiftly up a mountainous passage, followed by an interior view of the carriage in which several irate passengers are jostled and tossed about. One of the passengers, a young woman who utters the first lines of the movie, is Carla Laemmle, the niece of Carl Laemmle, Sr. She reads shrilly from a travel pamphlet: “Among the rugged peaks that frown down upon the Borgo Pass are found crumbling castles of a bygone age.” Carla remained incredibly proud of the part she played in starting off the 1930s Universal horror cycle until her death in 2014 at the age of 104.

A smartly-dressed, clean cut young man is seated amongst the carriage passengers. This is Renfield, played by Dwight Frye. Renfield asks the driver to drive slower, but another passenger tells him they cannot slow down, for they need to reach the inn before sundown. It’s Walpurgis Night, a “night of evil.”

The carriage careens into a small village square – nearly squishing a flock of geese in the process – where villagers appear relieved to see those on board arrive safely. Renfield requests that the driver leave his luggage on the carriage, as he plans to continue on to Borgo Pass to meet Count Dracula’s carriage at midnight. The villagers are completely flabbergasted, and stricken with fear. With a complete lack of subtlety on the part of the script writers, the innkeeper explains to Renfield that Dracula and his wives are vampires who take the form of wolves and bats and who feed on the blood of the living. Naturally, Renfield ignores these ultra-specific warnings and insists he has business at Castle Dracula that must be completed. The innkeeper’s wife gives him a cross to use for protection.

The scene cuts to Castle Dracula, for a series of images whose spookiness is only heightened by the lack of a musical score. The camera pans through a silent, spacious basement with vaulted stone ceilings and a dirt floor dotted with patches of dry ice. It focuses on a coffin lying in the dirt. The coffin’s lid slowly cracks open and a shaky hand slithers through the gap. The camera switches to a shot of a startled opossum running to hide behind a different coffin in response to a banging sound off-screen. Next we see the face of a woman revealed as she reaches out of her own coffin.

The shot that follows this sequence is perhaps the most mysterious bit of this whole movie, and it’s definitely my favorite shot. From behind, we see a bee crawling out of a bee-sized coffin. Actually, thanks to outtakes that show the front of the insect’s body from the Spanish language version of Dracula, which was filmed simultaneously with the English language version (and which I will talk about in its very own blog post), we know that it is not in fact a bee, but rather a Jerusalem cricket. To make matters more confusing, this creature is neither a real cricket nor from Jerusalem. In English Dracula, we only see the Jerusalem cricket from behind, suggesting that we are supposed to think it’s a bee. This shot alone begs hundreds of questions: Is it supposed to be a normal-sized bee in a tiny coffin? Is it a human-sized bee in a normal-sized coffin? Is the bee a vampire? How does a bee become a vampire? Why is a bee hanging out with Dracula et al.? Why did Tod Browning include this shot? Did they find a random Jerusalem cricket on the street or did they have to contact an agency and draw up a contract? Where did this Jerusalem cricket go after his big break? During filming was he squished by accident? On purpose?

Every time I watch this movie, I’m so taken aback by the appearance of the vampire bee that the next shots, of a wife sitting up in her coffin and the first time we see Dracula, lose a bit of the force that is intended to accompany them. Dracula stands in the basement with his eyes penetrating, unblinking, and lit by small spotlights. His wives, dressed in flowing nightgowns, drift out of their coffins, their movements poised and slow. Wolves howling in the background cut through the creepy silence.

We meet up once more with Renfield, whose carriage has arrived at Borgo Pass. Dracula waits for him, barely disguised or covered, seated atop his own carriage. Renfield’s driver chucks his luggage out, hardly stopping in the process, and then peels away. A confused Renfield boards Dracula’s carriage, but not before looking the vampire in the eye, seeing his face, and speaking to him. For some reason, Renfield will not remember that the man driving his coach is the very same man he meets just minutes later at Castle Dracula. Perhaps it is because he is once again subjected to a fast and jerky ride to the castle – a bump to the head, short term amnesia? For the second time in one day Renfield calls out to the driver to slow down, but to his surprise, the driver has been replaced by a bat on strings which hovers above the driver’s seat. At this point, I think I would’ve booked it, but Renfield is a man of business and he stays the course.

Renfield enters the derelict front hall of the castle, observing the cobwebs, crumbling walls, and disintegrating furniture while Dracula slowly descends the grand staircase. It is at this point that we are introduced to another member of Dracula’s mysterious menagerie: the armadillo.

This one I can almost explain, though. There are a few theories as to why a creature native to South America makes an appearance in the Count’s Transylvanian residence. The first is that Tod Browning wanted to place exotic, otherworldly animals throughout Dracula’s castle, and since most moviegoers in the 1930s had probably never seen one before, an armadillo fit the bill. Another idea is that censors at the time didn’t like for rats to be shown in films, and that opossums and armadillos resembled rats enough to act as stand-ins. Yet another theory is that the armadillo was intentionally chosen to play into commonly-held beliefs about the creature. They are often found snooping around graveyards and are said to enjoy the flesh of the newly-deceased, much like our vampires. And finally, the most intellectual explanation is that vampires have long been associated with disease epidemics – largely due to the disease-carrying nature of bats. Armadillos, too, are known for their ability to transmit disease. Specifically, they can carry and spread leprosy, a disease characterized by a loss of sensation and overall weakness – a fairly good metaphor for death by vamp bite.

Or maybe Dracula took a trip to Mexico and thought the armadillos were cute enough to bring home with him. We’ll never really know.

Dracula halts his descent of the grand staircase and utters one of the most iconic lines in cinema: “I am… Dracula.” Renfield expresses his confusion over… well, everything we’ve witnessed for the past ten minutes, to which Dracula responds (again, iconically): “I bid you welcome.” Without further comment he turns, leading Renfield up the staircase. They are stopped by the howl of a wolf outside the castle. Dracula once again turns and says the third most famous quote in this movie: “Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make.”

The vampire retreats back up the staircase, passing through a massive spider web without disturbing it. When Renfield trepidatiously follows him, he requires his cane to slash through the web. A huge spider scurries up the wall. Dracula says (randomly, with no context given): “The blood is the life, Mr. Renfield.”

Dracula leads Renfield into a more welcoming room, with a cheerful fire burning, a bed made, and a table set for dinner. The vampire immediately gets down to business. Renfield is a real estate agent who has traveled to Transylvania (without telling anyone of his whereabouts) to bring the Count the lease for Carfax Abbey, a property in England which Dracula has purchased. It’s unclear as to why Renfield couldn’t have sent the paperwork through the mail.

In the process of putting away the paperwork, Renfield cuts himself on a paperclip. He dramatically squeezes just beneath the wound, forcing a bead of blood to sit precariously on his fingertip. Dracula prowls menacingly toward the realtor but recoils when the cross from the innkeeper’s wife falls across Renfield’s hands, protecting him.

After watching Renfield suck the blood off of his finger, Dracula grabs a bottle of wine and pours the realtor a glass. When Renfield inquires as to whether Dracula will also partake, the Count says: “I never drink… wine.” We can guess from the absolutely sinister smile on Dracula’s face while Renfield drinks that the wine must have been drugged. The vampire leaves, allowing Renfield his privacy.

Renfield immediately starts to feel the effects of the drug, stumbling to open the floor-to-ceiling windows while Dracula’s wives stealthily approach. I should note that, while I refer to them as “wives” or “brides,” neither in the novel nor in this movie are they ever referred to as such. We don’t truly know their relationship to Dracula. The wives in this film are played by Geraldine Dvorak, Cornelia Thaw, and Dorothy Tree.

A bat on strings flies in front of Renfield and he passes out. The wives close in, ready to pounce. Before they can indulge in the true delicacy that is an English realtor, Dracula steps through the window and motions for them to back away. He crouches over Renfield’s body, leaning toward his neck, and the scene fades to black. It is thought that the bite itself was never shown due to the sensibilities of the censors, who might have seen the homosexuality inherent in a man biting another man’s neck. Indeed, the other victims of Dracula are all women, though we never see fang-to-neck contact with them either.

We next see Renfield aboard the schooner Vesta, a ship bound for England that has encountered difficult weather. All scenes of the boat and crew during the storm were repurposed from Universal’s The Storm Breaker (1925), which accounts for the noticeably worse visual quality of these scenes. Renfield also looks worse for wear, his perfectly-coiffed hair falling across wide, mad eyes and his voice raspy while he cracks open Dracula’s coffin: “Master, the sun is gone.”

The ex-realtor’s newest passion appears to be obtaining blood – from lives, not human lives, but “small ones.” Dracula seems to have promised Renfield those lives in return for his loyalty. Unfortunately, the only lives Dracula is interested in at the moment are those aboard the Vesta. Once it makes port, the captain is found dead, tied to the wheel, and the rest of the crew is dead along with him. Here’s a fun fact: Tod Browning makes an uncredited cameo in this sequence as the voice of the harbor master who discovers the carnage aboard the Vesta.

Police inspectors are led below deck by Renfield’s maniacal laughs and groans. We see a newspaper article about the incident which states: “Sole survivor a raving maniac. His craving to devour ants, flies and other small living things to obtain their blood, puzzles scientists. At present he is under observation in Doctor Seward’s Sanitarium near London.”

I do want to interject here to clarify that insects don’t actually have blood – not the same kind of hemoglobin-rich substance that vertebrates have, anyway. So while the concept of Renfield craving bugs is gruesome and disgusting, as intended, in reality Renfield would be better off chowing down on an armadillo.

Cut to the dark, foggy streets of London, car horns honking. Dracula, in a cloak and top hat, approaches a flower girl. Rather than accept a flower, he leans into the woman, grabbing her shoulders and pulling her behind a building as he bares his teeth at her throat. A scream cuts through the car horns. Dracula walks slowly, as if in a trance, away from the scene of the crime, right into a theater.

There’s a short sequence that happens between Dracula entering the theater and his meeting the Sewards in their box that I’ve always liked. An usher approaches to show the vampire to his seat, and I’ve always thought he looked completely overwhelmed by the opera before she leads him to the Sewards’ box. Over the course of the film, Dracula is presented as a bizarre, otherworldly creature who is distinctly different from the mortal men around him – and he seems to revel in that difference. But in this short scene, we see the vampire stripped of that confidence and finally feeling like the alien that he is. And it makes sense that a creature who has lived centuries in an ancient castle separate from humanity wouldn’t know what to do when confronted with a modern social situation. It’s perhaps the only time we see anything slightly human or sympathetic about the Count, and it’s a bit of subtlety for which I believe Bela Lugosi deserves considerable credit.

Dracula uses his powers of persuasion to direct the usher to enter the Sewards’ box and relay a message to Dr. Seward that he is wanted on the telephone. The vampire uses this opening to introduce himself to the doctor, whose sanitarium just so happens to be right next door to Carfax Abbey. Dracula also makes the acquaintance of Mina Seward (the doctor’s daughter), her friend Lucy Weston, and Mina’s fiancé, John Harker. They discuss how nice it will be for someone to live in the Abbey, and how much work it will take to fix it up. Dracula states that he won’t make any repairs, he likes his castles old and crumbling.

Lucy, clearly taken by the count, says that the Abbey always reminded her of that old toast: “About lofty timbers, the walls around are bare, echoing to our laughter as though the dead were there. Pass a cup to the dead already, hurrah for the next one who dies.” This is an excerpt from a 19th century poem by Bartholomew Dowling called “The Rebel.” Lucy’s macabre outburst understandably makes her friends uncomfortable, but Dracula realizes he has found a comrade soul, as he merely replies, “To die, to be really dead, that must be glorious.”

These two were made for each other.

After the opera, the two women sit in Lucy’s room while Mina mocks Dracula’s melodramatic speech using a Hungarian accent. This is probably the first time anyone ever put on a typical “Dracula accent.” Lucy doesn’t find it funny, though. She is smitten with the strange Count. Unfortunately for her, he shares the sentiment. While Lucy is lying in bed that night, a bat flies through her window. The Count changes into his human form and we see him lean in to bite her neck. Again, we don’t see the actual bite.

Our next scene is in Dr. Seward’s medical amphitheater, where Lucy’s body lies before rows and rows of observing doctors. The doctors attending her futilely attempt to give her blood infusions to replace the unnatural loss of blood she has suffered. They observe two unusual puncture marks on her neck.

If you’ve been missing Renfield, have no fear. We briefly meet up with him again amidst the howls and screams of the Sewards’ sanitarium. Renfield is yelling at and protesting to one of the orderlies, named Martin, who functions as the comic relief character in this film. Martin pries a spider out of the ex-realtor’s grasp and throws it out the window. He berates Renfield in a thick cockney accent. Personally, I don’t think spider-eating is that big of a problem in the grand scheme of things. I feel that Martin should probably focus his attention to more pressing matters, like keeping Renfield contained in his room. We soon learn that Renfield has a knack for escaping and wandering the grounds of the sanitarium.

Next we meet Professor Van Helsing in his laboratory as he studies a sample of Renfield’s blood under a microscope. After careful inspection he declares to Dr. Seward and the other physicians around him: “Gentlemen, we are dealing with the undead.” He further clarifies that it is a nosferatu, or a vampire.

The great Edward Van Sloan plays Professor Van Helsing, and though this is not his film debut, it is the part for which he first became widely recognized. Van Sloan had previously played the part of Van Helsing in the 1927-28 Broadway production of the stage play Dracula. He was cast in the 1931 film due to his connection with the theater production, in the hopes that audiences of the successful theatrical version would be compelled to see his performance on the silver screen.

Dr. Seward obviously doesn’t believe Van Helsing’s assertion that there is a vampire in their midst, but he allows the professor to meet Renfield face-to-face. The meeting does not start strong, with Renfield immediately losing his cool and begging Dr. Seward to send him away from the sanitarium so that his cries at night don’t disturb Mina. After Van Helsing pulls a sprig of wolfbane out of his wallet (should we all keep some in case of emergencies?) and Renfield recoils, Martin takes the “fly-eater” back to his room.

Amidst the howling of wolves, Dracula appears at Renfield’s window and uses his powers of persuasion to compel Renfield to do… something. The exchange appears to take place entirely in the characters’ heads, but Renfield does verbally protest the order, saying, “Please don’t ask me to do that. Don’t – not her.” We can assume he is talking about Mina.

Speaking of, we cut next to Mina asleep in her room. A bat flies outside her open window, and then we see Dracula standing in Mina’s doorway. He approaches her sleeping form and we see him closing in on his prey, but again the scene cuts to black before we see an actual bite.

Mina sits in the library, scarf draped inconspicuously around her neck as she recounts her bad dream from the night before to Harker. She recalls a mist covering her bedroom, and then two glowing red eyes on a livid face that descended upon her. Van Helsing and her father enter the room, and the professor begins questioning her about her dream. In an aside, Harker – who is incredibly smart and perceptive – says to Dr. Seward that “there’s something troubling Mina.” Van Helsing inspects Mina’s neck and finds two small marks.

Right after Harker asks what could have caused the marks, the Sewards’ housekeeper announces Count Dracula’s presence from the hallway. The vampire greets Dr. Seward and then turns his attention to Mina, who is making moony eyes at him. Van Helsing interrupts Dracula’s compliments toward Mina, leading the doctor to introduce the vampire and the professor. The two size each other up. Dracula appears to be familiar with Van Helsing.

The vampire says that he hopes his stories from the night at the opera weren’t the cause of Mina’s bad dreams. Harker gets huffy at the vampire’s overfamiliarity with his fiancée and pouts his way over to a cigarette box. While the others converse, Van Helsing notices that Dracula does not have a reflection in the mirror attached to the lid of the cigarette box. Mina excuses herself to go to bed, and before Dracula makes his exit as well, Van Helsing shows him the inside of the box. Dracula immediately recoils and slaps the box out of the professor’s hands. He makes his apologies to Dr. Seward, claiming that he dislikes mirrors and that Van Helsing would explain. He then exits the house via the terrace.

Harker follows him out onto the terrace and yells when he spots a wolf running across the lawn. Van Helsing takes this opportunity to explain to the other men that Dracula is a vampire, which is met with reasonable doubt. While the men are discussing matters, Mina leaves the house and meets Dracula on the lawn. They embrace and he wraps her in his cape.

Back in the house, Renfield’s manic laughter interrupts Van Helsing’s conjectures about vampires. He emerges from where he had been eavesdropping behind a door and insists to Dr. Seward that he should listen to Van Helsing. He begs Harker to take Mina away from the sanitarium, but is interrupted by the squeaking of a bat in the window. Renfield cowers in fear before Harker shoos the bat away.

A housekeeper screeches and runs into the room, exclaiming that Mina is dead on the lawn. The men race outside, leaving her with Renfield, who laugh-moans menacingly. She faints at the sight of him, and we watch as Renfield crawls toward her limp body, reaching for her throat. It would seem he has finally graduated from spiders to people. The scene cuts away before we see any harm befall the housekeeper. Apparently the original shot included a fly on the woman’s neck that Renfield was reaching for, but the implied descent into madness that the final edit implies is much more frightening. However, this change does cause a slight continuity error when we see the housekeeper later on, clearly unharmed.

Harker carries a still-living Mina back to the house as Dracula watches from behind a tree. We cut to the front gates of a cemetery, where we can hear a child crying off-screen. Lucy, dressed in a white gown, walks slowly down a wooded path, eyes wide open and staring blankly in front of her. The following morning, Martin and a couple of nurses at the sanitarium read an article in the paper about a woman in white who commits attacks on small children after dark.

This subplot is one of the greatest production tragedies of this film. The idea of a vampire woman stalking the children of London is absolutely chilling, and yet Tod Browning made very little use of it. Part of that was likely due to concerns about the censors, but most of it came down to budget. The cemetery scene is the first and last time that we see Lucy as a vampire, but it was not meant to be so in the final shooting script. A scene was written in which Van Helsing and Harker track down Lucy in her family’s vault in the cemetery. Harker kills her with a stake to the heart, allowing her to rest in peace. It seems that this scene was never filmed and the expensive vault set never constructed. This is a shame, as the Lucy subplot goes unresolved in the final cut of the movie. Mina seems largely unaffected by the death of her friend throughout the film, and at the end Lucy is not dealt with – which could have been an excellent angle for the sequel, but alas Universal missed that opportunity.

On the terrace at the Sanitarium, Mina does acknowledge to Van Helsing and Harker that she saw Lucy once after her death outside her window. Van Helsing promises to try and save her soul (he breaks this promise) and then leaves to allow the couple their space. Mina tells Harker that she can no longer be with him due to Dracula’s hold on her. He attempts to convince Mina to leave the sanitarium with him, to no avail. Mina chooses to stay.

Van Helsing explains that Mina will be safe so long as she stays in her room. Her room has been covered in wolfbane and he additionally instructs a nurse to keep a wreath of wolfbane around her neck overnight. He also states that the windows must remain closed.

Of course, that’s not how things shake out. The men convene downstairs in the library, where they are once again interrupted by an escaped Renfield. The ex-spider-eater appears to have gained a new craving for rats, as he explains madly to all present. The men are alerted to Dracula’s presence in the house, and all but Van Helsing run out of the room to find him. Dracula steps into the library from the terrace to confront the professor. This confrontation is when we learn the stakes of that night: if Mina dies by day, her soul will be saved. If she dies by night, she will become a vampire. When Van Helsing threatens to destroy Dracula, the vampire attempts to use his powers of persuasion to bring the professor closer. Van Helsing fights the mind control and draws a cross from his pocket, which sends Dracula running.

Upstairs, an agitated Mina complains to Nurse Briggs about the wolfbane in her room. Harker arrives, and the nurse explains to him that she briefly became dizzy and then found Mina awake and on the terrace, refusing to go back to bed. Harker goes to comfort his distressed fiancée. Mina quickly calms down, claiming that she has never felt better. This is enough to convince Harker that all is well, and he dismisses the nurse. The two lovers admire the stars from the terrace. While Harker’s neck is craned, Mina stares raptly at his neck, leaning in closer and closer until he looks back down at her, breaking the spell.

A bat on strings swoops down onto the terrace. As Harker attempts to shoo it away, Mina appears to have a conversation with it. She explains to Harker that he must steal and hide Van Helsing’s crucifix. In an excellent bit of acting from Helen Chandler, her eyes turn feral and she moves as if to pounce on her fiancé. Just before she can do so, Van Helsing jumps in with his crucifix to separate them.

Mina is distraught and admits to Harker that everything the professor has said about Dracula is true. He came to her in the night and made her drink from a vein in his arm.

And then this high-octane scene is broken by the sound of a shotgun in the night. Martin is standing on the lawn with the housekeeper who was almost Renfield’s snack, holding a shotgun in an attempt to shoot the bat on strings. Van Helsing tells him that it would take more than a bullet to get rid of that bat.

Later that night, Mina is asleep in her bed. Dracula persuades Nurse Briggs to get rid of the wolfbane on the door and let him into the house. He lifts Mina from her bed and uses his powers of persuasion to direct her to Carfax Abbey. Renfield has again escaped and is making his way to the Abbey when he is spotted by Harker and Van Helsing, who follow him. At the Abbey, Renfield excitedly runs up a long staircase to his master, asking for orders. When Harker shouts from the window for Mina, Dracula becomes enraged that Renfield had led the men to the Abbey. He chokes Renfield and throws him down the stairs to his death.

As Harker and Van Helsing enter the Abbey, Dracula carries Mina to the basement. Mina screams and they hurry to follow, looking frantically for her. Van Helsing finds Dracula’s coffin, with the vampire already asleep inside of it in a last-minute attempt to avoid the rising sun. Mina is not in the second coffin, prompting Harker to run off in search of her in the hope that she is still alive. Van Helsing drives a wooden stake from the coffin through Dracula’s heart, and off-screen we hear his dying moans. Interestingly, those moans were removed from initial screenings of the film and were only added back decades later on the DVD release.

Van Helsing and Harker don’t find Mina in the second coffin

I can only imagine if you’ve made it this far (THANK YOU) you’ve probably cottoned on to the fact that I adore this movie. Even still, I’m the first person to admit that it’s not without flaws. The film’s edit is arranged in a way that creates quite a few continuity errors – it seems as though an entire nocturnal visit from Dracula to Mina’s bedroom was shot and then cut from the final edit, with pieces of the deleted scene spliced into the remaining visit scene that have Dracula seemingly teleporting throughout the room. Lucy’s storyline is never resolved, leaving us to believe that our heroes are simply going to allow the child-eating Woman in White to go about her business unchecked. Harker’s role – and, to a degree, Mina’s as well – is reduced so significantly compared to the novel that he often comes across as a vapid idiot with almost no relevance to the overall plot.

When Dracula dies, Mina clutches at her heart, as if she too has been staked. She is released from the vampire’s spell. Harker and Van Helsing find her, and she explains that the daylight stopped him from killing her. The lovers leave the basement of Carfax Abbey, leaving behind Van Helsing, who has some unnamed business there still. Perhaps it has to do with Dracula’s body. Perhaps he means that Lucy still needs to be taken care of. We’ll never know.

And then we get the end card. It’s certainly an abrupt ending by modern standards.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Unfortunately, his career after the release of Dracula was not quite so joyous for poor Bela. But I’ve rambled for long enough – we’ll certainly meet Mr. Lugosi again, and you’ll certainly hear “poor Bela” from me many more times.

But for now, a HUGE thank you for sticking around! Drop me a comment if you remember the first time you saw Dracula. I’d love to know your thoughts about this film. I hope you’ll come back next time, when we travel a few decades into the future to visit a college professor in possession of an incredibly old fish.

A common criticism I’ve heard is that the movie feels very stagey, like we’re watching a stage play rather than a film. I think this is a fair criticism if you come into this movie expecting it to be a faithful adaptation to the book. But we have to remember that this movie is an adaptation of the stageplay, so the staginess is understandable. We must also remember that the reason it took more than a decade to finally make this movie was because studios in the 1920s recognized that a sweeping, atmospheric film following the original novel was outside of the realm of possibility for filmmakers at the time.

And to all of these criticisms I say this: not a single negative aspect of this film could possibly eclipse the incredible, groundbreaking artistry that went into its production.

In Dracula, Browning creates one of the most iconic and impressive gothic atmospheres in film history – armadillos and all. Dwight Frye gives a showstopping performance as a completely maniacal Renfield. He steals every single scene he’s in with his psychotic laughter and genuinely terrifying wide eyes and bared teeth. Unfortunately for Frye, whose main concern in taking this role was being typecast, his outstanding performance in this film sentenced him to a career of psychotic maniac roles.

And Bela Lugosi. What is there to say about Bela Lugosi that hasn’t been repeated ad nauseam by people far more knowledgeable than me? There’s a reason why, when asked to picture Dracula, every single person alive today thinks of a pale, well-dressed man sporting a long cape and medallion, with a widow’s peak and an Eastern European accent. Lugosi created our general cultural knowledge of what a vampire is. When kids pretend to be Dracula, they parody his slow, lilting way of speaking. No matter how many times I watch this movie, I always get a little electric jolt of glee whenever he appears on screen. He is pure joy to watch as Dracula.