Few figures of old Hollywood fascinate me in the way that Helen Chandler does. Known for her understated and – in my opinion – underappreciated performance as Mina in Dracula (1931), her extensive career on stage and screen and the tragic final years of her short life have been largely forgotten.

Helen Chandler was born in New York City on February 1, 1908 – probably. She has also been credited for a birth in 1906 in Charleston, South Carolina and in 1909 in New York City. The confusion likely arises from her habitation of both cities throughout her childhood, along with poor record-keeping.

In Charleston, where her younger brother Leland Chandler was born, her father, Leland Sr., was a horse breeder and racer. Chandler accompanied her father to his races throughout the South, a pastime that she credited for her love of the theater. In an interview for The New Movie Magazine (January, 1932), she recalled:

“It wasn’t the horses that interested me particularly. It was the crowd, the clamor and the excitement. I adored watching the people. They were so gay, so taken out of themselves. It had the feeling of theater – good theater. Of course, I didn’t realize it then, but this is probably where I first wanted to be an actress.”

Laws in the South prohibiting race track betting reportedly inspired the family to move back to New York City. It was here that Chandler made her acting debut in Barbara at the Plymouth Theatre on November 5, 1917 at the ripe age of nine (though her exact age depends on when you believe she was born). Broadway credits quickly accumulated.

Chandler quickly became one of the most in-demand stage actresses in New York for the next decade. Her great success meant that she met and worked with many notable figures in the industry, including some of the actors and producers who would become mainstays of the horror genre in film. For example, in 1925-1926 she played the role of Ophelia in a modern-dress (flapper fashion) production of Hamlet. The play was produced by Horace Liveright, who two years later would produce the stageplay Dracula with Bela Lugosi in the titular role.

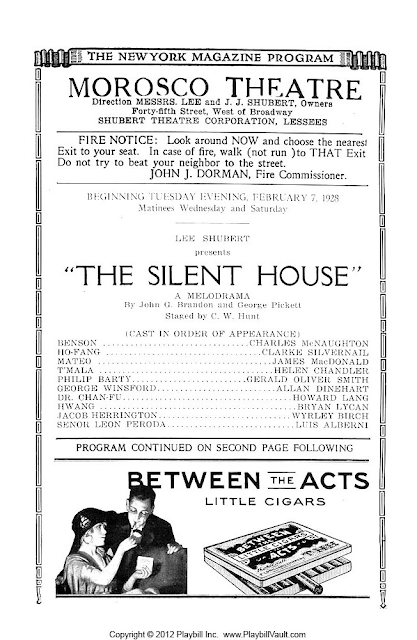

The horror connections didn’t stop there. In 1926-1927, Chandler performed in The Constant Nymph, which also featured future Invisible Man star Claude Rains and his then-wife, Beatrix Thomson. Then, in 1928, she starred in the horror play The Silent House. The New York Times had the following to say about the play:

“What a rigamarole of bare-faced nonsense! Hidden doors open. Bodies topple on the floor. People spit across the room… In the big scene, the stealthy Dr. Chan-Fu claps the artless maiden into a lethal closet; and while the hero is hunting her desperately, poison gas fills the room, whistles blow eerily, monsters with lighted eyes hiss, and the grim reaper gives every evidence of lurking confidently in the wings.”

It sounds like this production was exactly my kind of bare-faced nonsense. While the New York Times’ reviewer might not have fully enjoyed the play, there was at least one member of the audience who left thoroughly impressed. Reportedly, Tod Browning attended one of Chandler’s performances in The Silent House and would remember her two years later while casting for the film version of Dracula.

Chandler made her silent film debut in The Music Master (1927), which was filmed at Fox’s New York studio and is unfortunately now a lost film. Later that same year, having taken a liking to film acting, she traveled to Palm Beach, Florida for a part in The Joy Girl. This film contained some of the earliest two-strip Technicolor scenes. A print of it is now housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Soon after The Joy Girl, Chandler found herself at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland for John Ford’s Salute (1929), which is notable for an uncredited early performance by John Wayne.

Chandler returned to Broadway for a short stint, but soon reluctantly “went Hollywood,” in spite of her belief that she didn’t fit in there. She told the Los Angeles Examiner: “I’m not pretty and I don’t belong in pictures.”

Which is completely laughable coming from a woman in possession of such ethereal beauty and a striking screen presence, but okay, Helen.

Upon her conversion to silver screen actress, Chandler starred in Sky Hawk (1929), Rough Romance (1930), and, most notably, Outward Bound (1930). Outward Bound is one of the very few films of Chandler’s that I’ve been able to track down and watch. It’s a fantastical picture about a young couple who find themselves aboard an unmanned, fog-cloaked ship sailing to an unknown destination. Slowly, they and the other passengers realize that they are all dead and en route to their final judgment. It is revealed that the young couple committed suicide, which means they are not on the passenger list and cannot be given judgment. I won’t spoil the ending, but if you like films with dogs who save the day, this one might be for you.

Outward Bound is unlike any other movie I’ve seen from this time period. The pre-Code discussion of suicide is certainly different from what I’m used to seeing on the silver screen, and while Chandler didn’t have a whole lot to do she still managed a fairly haunting performance (cue rimshot). Variety seems to have agreed with my assessment: “Helen Chandler is still the same sobbing contralto and in that kind of voice, suits her role with acting to measure.”

Chandler married Cyril Hume on February 3, 1930. Hume was a British novelist and playwright who notably wrote the sci-fi horror film Island of Lost Souls (1932) for Paramount. The couple initially kept their marriage a secret, moving to a house in Hollywood Hills with Hume’s five-year-old daughter from a previous marriage.

Meanwhile, Chandler was receiving a fair bit of attention from the press – who dubbed her “The Chandler” – for her burgeoning film career. She was known by the public to love Romeo and Juliet, to the point of carrying a small copy on her person as a good luck charm. Reportedly, she became “frantic” and “shivering” if she ever misplaced it. Chandler’s greatest professional wish was to someday play Alice in Alice in Wonderland. She kept a garden toad and a small white cat with bright blue eyes named Blue Bell as pets. She hated makeup, slinky dresses, and high heels. She admitted she was a financial disaster and never paid bills because she thought utilities “were part of the house.” Chandler lost her first year’s earnings in Hollywood in a construction investment bank.

It’s here, in her flippant self-proclamations of financial illiteracy and disdain for the glitz and glam of her profession that we glimpse a fascinating aspect of her personality. Chandler was largely irreverent in speaking about herself and her career, which to me is incredibly endearing. She spoke of her screen work in Hollywood in the following way:

“I thought there was no place here for me at all. For a couple of months, my agent wore out the tires trying to peddle my charms. Nobody had ever heard of me. At interviews I would be told to do a little song and dance. ‘But I’m a dramatic actress!’ I would argue. They would just smile soothingly – and tell me to dance.”

Her next big film was Mother’s Cry (1930), in which she worked alongside future Dracula costar David Manners. In an interview with Gregory William Mank in 1976, Manners declared that Chandler was his all-time favorite costar. This is high praise coming from someone who, during his 7-year career in Hollywood, starred alongside such actors as Loretta Young, Ruth Chatterton, Barbara Stanwyck, Kay Francis, Katharine Hepburn, and Carole Lombard. In my review of Dracula I was rather unkind to David Manners. Knowing that he adored Chandler almost makes me forgive his numerous transgressions. Almost.

The horror connections don’t stop here, though – Dorothy Peterson was top-billed for Mother’s Cry. She played Lucy in the original Broadway production of the American version of the Dracula stageplay with Bela Lugosi. I can’t help but wonder if Peterson wanted the role of Mina in the film version of Dracula, and if she felt slighted when she was overlooked in favor of Chandler.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the other horror icon present in the cast of Mother’s Cry: a little-known actor called Boris Karloff who played an uncredited murder victim and was a year away from massive stardom from his starring role in Frankenstein.

And then came the film for which Chandler is still renowned to this day: Dracula. However, Chandler never saw her role as Mina Seward as significant. She said:

“It would be an awful fate, for instance, to go around being a pale little girl in a trance with her arms outstretched as in Dracula, all the rest of my screen career!”

In spite of her general disdain for the part, Dracula skyrocketed Chandler to a considerable level of fame. Unfortunately, she was not doing quite as well in her personal life. After filming wrapped on Dracula each day, she returned home to Hollywood Hills to a marriage that was crumbling. David Manners recalled that Cyril Hume was “a Prohibition-era Svengali of alcohol,” meaning he negatively influenced Chandler’s drinking habit. The marriage ended in 1934 but she would struggle with alcoholism for the rest of her life.

There was another difficulty Chandler faced during the filming of Dracula, which she described in an interview with Ruth Rankin:

“In Dracula, I played one of those bewildered little girls who go around pale, hollow-eyed and anguished, wondering about things… I was. Wondering about when I could get to the hospital and part with a rampant appendix without holding up the picture.”

Chandler’s final day of filming on Dracula was November 13, 1930. On November 14, reportedly less than 12 hours after filming wrapped, she underwent an appendectomy at Hollywood Hospital. She had spent the entirety of the 6 weeks of filming in excruciating pain due to a troublesome appendix. I think that that’s worth keeping in mind while watching her performance – and perhaps it explains away complaints of a stiff or distant performance on her behalf.

The whole ordeal of Dracula seemed to have left a mark on Chandler in more ways than one. She emerged from the film in need of a new type of role. On April 15, 1931, just two months after Dracula’s release, she told Marquis Busby in an interview for the Los Angeles Examiner:

“I think I am much more funny than I am tragic… No one will ever give me a chance to be funny in a picture. I do get awfully tired of being tragic all the time.”

These words sound ominous now, considering the tragedy that would befall her later in life.

Over the next several years Chandler would bounce back and forth between filming in Hollywood and performing on Broadway. Not long after Dracula’s release, she fell into Poverty Row films such as Mayfair Studios’ Alimony Madness (1933), a short and sweet drama about a husband who can’t keep up with his ex-wife’s exorbitant alimony payments and his new wife’s unconventional solution to their resulting monetary woes. Chandler plays the part of the new wife who ultimately shoots the ex-wife after her alimony payments interfere with the couple’s ability to seek medical attention for their sick baby (who dies due to lack of medical care). The film is 67 minutes of legal talk and money troubles, with a rather bleak outlook on divorce and an incredibly abrupt ending. Of all the films I’ve seen featuring Chandler, Alimony Madness gives her the most to do. Her signature quivering voice is ever-present, but in this film she carries herself and delivers her dialogue with a degree of spunk and strength that is refreshing to see from her. Alimony Madness is streaming for free on Tubi for those who might be interested – I’d recommend giving it a try.

On August 22, 1933 the Los Angeles Examiner reported that Chandler had tested for the role of Alice in Paramount’s Alice in Wonderland. The article claimed that “The chances are very much in her favor.” In what must have been a low blow, Chandler lost out on the much cherished role, which was instead given to Charlotte Henry.

It was back to Broadway for a stung Chandler.

In 1934 she co-starred with Bramwell Fletcher in These Two at the Henry Miller’s Theatre. English-born Fletcher had also found much fame on the London and Broadway stages, as well as in horror films; he had roles in Svengali (1931), The Mummy (1932), and The Monkey’s Paw (1933). I personally remember him best for his role in The Mummy as Ralph Norton, the archeologist’s assistant who initially encounters the mummy and devolves into a raving, scream-laughing lunatic at the mere sight of the bandaged fellow.

By September of that year, The Los Angeles Examiner commented that Chandler and Hume’s marriage was “said to be heading for the rocks.” They were divorced soon thereafter and Chandler fled to England.

She returned with a new husband in tow: Bramwell Fletcher. Back in New York, the newlyweds starred in separate Broadway plays. Unfortunately, the marriage only lasted five years. The couple divorced in April 1940, possibly in large part due to Chandler’s alcoholism.

In the summer of 1940, following her divorce from Fletcher, Chandler entered the La Crescenta Sanitarium with a nervous breakdown. She did recover in time to join a production of Tonight at 8:30 at the Curran Theatre in San Francisco.

Chandler’s final film appearance was in 1938 in Mr. Boggs Steps Out. Her final stage appearance was in July 1941 in a revival of The Show Off. She had reached the end of her career at age 35.

No one seems to know exactly when she married again, but at some point after she faded from the spotlight she found herself married to Walter Piascik. Piascik was a merchant mariner who was reportedly a “big, dumb man who didn’t talk too much.” I’ve read sources which claim that Piascik shipped out of San Francisco soon after their marriage and never returned, but I haven’t been able to confirm these statements. It’s unclear how long they were married – most of Chandler’s obituaries named him as her husband, but we do know that they divorced at some point before her death.

And then, on November 9, 1950, tragedy struck. A headline in the Los Angeles Daily News read: “Fire in bed hospitalizes ex-actress.” I’ve copied the article below:

“Former film star Helen Chandler, 44, was found badly burned and unconscious today in bed in her Hollywood apartment.

She was taken to Hollywood Receiving hospital, where her condition was described as serious. Presumably she had fallen asleep while smoking a cigaret [sic].

The unconscious woman was discovered by Sam Cox, manager of the apartment house at 1825 North Whitley terrace, who was compelled to remove the lock on her door to gain entry after smelling smoke.

The victim, clad only in a bed jacket, lay on the bed, severely burned on the left side of the face, head, neck, abdomen and leg. A rug covering the floor of the adjacent kitchen was smouldering, apparently fired by a burning nightgown the woman had discarded.

She gave hospital attendants her name as Mrs. Walter Piascik and said her husband, a merchant seaman, had shipped out three days after their arrival here from San Francisco.

Questioned later, however, she identified hersalf [sic] as Helen Chandler, who had star billing in approximately 35 films before retiring in 1938.

She last appeared on the stage here in “Boy Meets Girl” with actor Bramwell Fletcher, to whom she then was married. She divorced both Fletcher and her first husband, author Cyril Hume.

Cox told police he first was aroused at 4 am by another tenant, who reported he smelled smoke in the corridor, but after investigating the manager returned to bed. It was not until three hours later that he, too, detected the odor of smoke and removed the lock to gain entry to the woman’s apartment.

He said she had registered with Piascik three days ago.

Investigators reported they found a quantity of sleeping tablets in the room. Personal papers gave the woman’s previous address as 1030 Fell street, San Francisco.”

A friend of Bramwell Fletcher reportedly read a copy of Fletcher’s unpublished memoir Thistleball, in which he spoke of his ex-wife’s tragic life after the fire incident. He told Films in Review (October 1990):

“Apparently, her alcoholism was so severe that it not only ended her film career as well as their marriage, but also succeeded in driving her literally into the gutter. Mr. Fletcher recounts that he happened to read a newspaper account… long after they had divorced, that she had been badly burned in a rooming house fire and that one side of her face had been severely and permanently scarred. The last he heard of her was from an acquaintance who had received a letter in the mid-1950s from an insane asylum in the desert southeast of Los Angeles signed by her. When he went there, he was told by the head nurse that, yes, they did have a patient who claimed to be Helen Chandler. Of course, it turned out to be her…”

Of course we can’t be completely sure how accurate this account is, especially given that it’s third-hand and potentially marred by the passing of decades. But what does seem to be true is that Chandler did suffer considerable damage to her face as a result of the fire and that she did withdraw completely from public life during this time.

On November 3, 1959, The Hollywood Reporter published an article stating that Chandler would be “making her first visit outside the walls of DeWitt State Hospital in five years, cured and ready for home placement…houseguesting in Palm Springs with Lillian Roth, once Helen’s No. One fan…”

Roth was an actress and singer whose own struggle with alcoholism was recounted in her bestselling autobiography I’ll Cry Tomorrow. The book was one of the first in which a celebrity discussed their struggle with addiction. Roth could certainly relate to Chandler’s lifelong affliction, and what’s more is that they had been classmates at the Professional Children’s School in New York City decades prior.

It’s unclear if Chandler ever did spend time with Roth, and how long she may have “houseguested,” but we do know that she spent her final years at 15 Paloma Avenue in Venice, California. I can’t figure out who she lived with – if anyone – but we do suspect that she and Walter Piascik were divorced at this point. Unfortunately, she continued to fall prey to the alcoholism that had haunted her for the majority of her life.

In April 1965 Chandler was admitted to the Los Angeles County Hospital for significant bleeding due to an ulcer. She underwent surgery on April 25 and at 9:15 a.m. On Friday, April 30, 1965, Helen Chandler died in the hospital due to postoperative renal failure and cardiac arrest. According to her death certificate, she was 56 years old.

Memorial services took place at the Pierce Brothers Hollywood Mortuary at 3 p.m. on May 3, 1965. There was reportedly a “very small audience.” For decades, Chandler’s ashes remained in the area below the crematory at the Pierce Brothers Chapel of the Pines called “Vaultage,” where the abandoned cremated remains of over 10,000 individuals are stored.

Chandler rested in obscurity until July 13, 2023, when, thanks to an online fundraising campaign led by researcher Jessica Wahl and Hollywood Graveyard Youtube channel creator Arthur Dark, her remains were reinurned in the Cathedral Mausoleum at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

Filmography

The Music Master (1927)

The Joy Girl (1927)

Mother’s Boy (1929)

Salute (1929)

The Sky Hawk (1929)

Rough Romance (1930)

Outward Bound (1930)

Mother’s Cry (1930)

Dracula (1931)

Daybreak (1931)

Salvation Nell (1931)

The Last Flight (1931)

Fanny Foley Herself (1931)

A House Divided (1932)

Vanity Street (1932)

Behind Jury Doors (1932)

Christopher Strong (1933)

Alimony Madness (1933)

Dance Hall Hostess (1933)

Goodbye Again (1933)

The Worst Woman in Paris? (1933)

Long Lost Father (1934)

Midnight Alibi (1934)

Radio Parade of 1935 (1934)

The Unfinished Symphony (1935)

It’s a Bet (1935)

Mr. Boggs Steps Out (1937)